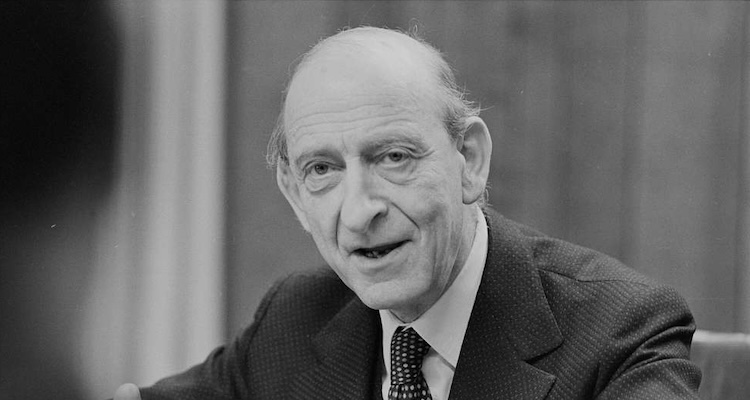

Nobody who is interested in writing about liberty can avoid Abraham Lincoln’s famous line on the topic: “The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty.” But why should this be so? The difficulty may have to do with a related question: Is liberty one thing or many things? Friedrich Hayek claimed that liberty is one thing, whereas “liberties appear only when liberty is lacking: they are special privileges and exemptions that groups and individuals may acquire while the rest are more or less free.” Hayek’s antagonists on this question included Raymond Aron, his fellow anti-totalitarian liberal. The great French political thinker, columnist, and Cold Warrior confessed his dislike for employing “liberty” in the singular. He devoted his last lecture at the Collège de France on April 4, 1978, to this very topic. Thanks to Princeton University Press, this last lecture is now available in English, paired with an epilogue by his longtime assistant, Pierre Manent.

Aron is most well-known in the United States for The Opium of the Intellectuals (reviewed in these pages in 1958), a lucid evisceration of the fallacies of the revolutionary and pro-Communist left. Yet Aron had an astonishing range of interests and competences—he authored more than 30 books in the disciplines of political philosophy, sociology, international relations, and comparative politics. He was also deeply engaged with the politics of his day—maintaining a weekly column in Le Figaro for 30 years before moving to L’Express and founding the journal Commentaire near the end of his life.

Aron defends his plural understanding of liberty by beginning from ordinary experience: We all face choices in our daily lives. We also understand that in order to enjoy some liberties, there must be prohibitions on certain other liberties that would prevent the exercise of our own. By recognizing the reciprocal requirement of restraints and prohibitions, Aron emphasizes the importance of liberty under law. His starting point is not the liberty of the state of nature, as it was for thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. Nor does he look to the revolutionary documents that declare our natural rights. Indeed, Aron criticizes the fourth article of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, which suggests that our liberty consists in the exercise of our natural rights and is limited only to the extent that such exercise harms others. He calls this formula “almost denuded of meaning.” What, after all, constitutes harm? In modern society in particular, how can we decide whether one’s economic activity harms others? Aron is thus dissatisfied with overly abstract and general approaches to liberty.

He proceeds instead by examining the content of our liberties in modern liberal democracies. Aron organizes these liberties into the categories of personal, political, and social. The first category includes security, or liberty against state coercion; liberty of movement (within one’s country and without); economic liberty; and liberty of opinion (religious and political). In the second grouping, Aron places the freedom to vote, protest, and assemble. By social liberties, Aron means the “material means for the exercising of certain liberties,” such as being educated. Social liberties would also include social security and what he calls the “liberty of collectives” (e.g., unions).

Aron makes a number of striking observations. He notices that these liberties, while often defined against the state, also exist thanks to a well-functioning state. The realization of free societies is rooted in the delicate interplay of authority, institutions, and self-restraint rather than in general theories or declarations of rights. Aron also rejects the Cold War dichotomy of “formal” and “real” freedoms. While his second category, “political” liberties, was often dismissed as merely formal by those on the left, Aron points out that voting and assembly are the “essential condition of the other liberties.”

Aron suggests that our “consciousness” of our liberty depends partly on the “consciousness of the legitimacy of the society.” Insofar as we define liberty “by the capacity of the power of doing, the more inequality appears to us unacceptable.” This is why modern liberal societies tend to reject or at least downplay their real and historically unique achievements in advancing liberties so long as inequalities persist. Aron says this is why many thinkers are tempted to place their hopes in an alternative arrangement that sometimes locates true liberty in community—or in a chaos approaching anarchy. Here, the words of his last lecture are particularly relevant to our times: “Failing to find a representation of the good society in Marxism or Sovietism, there is no longer a search for the good society but a total rejection of the existing society. This radical rejection sometimes takes a pacifist form, and sometimes takes a violent form.”

For Hayek, liberalism’s susceptibility to a sense of its own illegitimacy despite its concrete advances is rooted in confusion or imprecision about what liberty really is. In his view, liberty is best understood merely as the absence of coercion. Individuals are free to the extent that they can shape their actions according to their own will rather than to the will of others.

Aron believes in a definition of liberty as “intentional action, action which consists in choice and presupposes for the individual the possibility of doing and not doing.” For him, the crisis of liberal democracy is rooted in a false understanding of liberty as the liberation of our desires. To the extent that liberal democracy refuses to address the question of how to live a good life, the crisis will inevitably turn into a moral one. And it turns into a political crisis, because the liberationist ethic becomes the enemy of all prohibitions and institutions dedicated to moral formation and limits. If he is right, Hayek’s clear but narrow understanding of liberty is ill-suited to addressing such a crisis. For Aron, a healthy politics of liberty must hark back to an older understanding of liberty—in which people are free to the extent that they have some mastery over their passions. In modern society, such a person must accept the demands of citizenship and embrace liberty under law. “But what one no longer knows today in our democracies is where virtue is to be found,” he writes. “The theories of democracy and the theories of liberalism always included something like the definition of the virtuous citizen or the manner of life which would conform to the ideal of a free society.” That is no longer the case.

Thus, we sense Aron’s “civic unease,” as described by Pierre Manent in his excellent epilogue to this volume. Manent confirms that Aron is one of the greatest friends and champions of liberal politics that the West has ever had, but he suggests that this is precisely because Aron saw liberalism’s limits and blind spots. There is no better analogue for Aron, according to Manent, than Aristotle. For both thinkers, clear political analysis is rooted in “beginning from what is.”

Yet the popular temptation to approach the confusion of the world with a false clarity is why George Orwell wrote that “to see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” Raymond Aron never tired of that struggle.

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.