In the late summer of 1973, the U.S. Information Agency sent Commentary editor Norman Podhoretz on a lecture tour of the Indo-Pacific. He began in New Delhi, where he visited his friend Daniel Patrick Moynihan, then serving as ambassador to India. From there he proceeded to Australia, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Korea, and Japan. At each stop, he met with dignitaries, lunched with intellectuals, and delivered prepared remarks.

I recently came across the text of his speech. Reprinted later that year in the Australian journal Quadrant, Podhoretz’s words are not just relevant today. They reaffirm the mission of Commentary, 80 years old with this issue.

Podhoretz’s biographer, Thomas Jeffers, notes that the Asia trip took place in a bleak setting. Podhoretz still considered himself a centrist liberal, but the Democratic Party had turned to radicalism by nominating South Dakota Senator George McGovern as its presidential candidate in the previous election.

McGovern was the avatar of what Podhoretz called the “new liberalism,” an ideology of repudiation that indicted America for inequality, imperialism, and racism. For several years, Podhoretz had been using the pages of Commentary as artillery in an intellectual war against the new liberalism’s foundational ideas. It was a rearguard action.

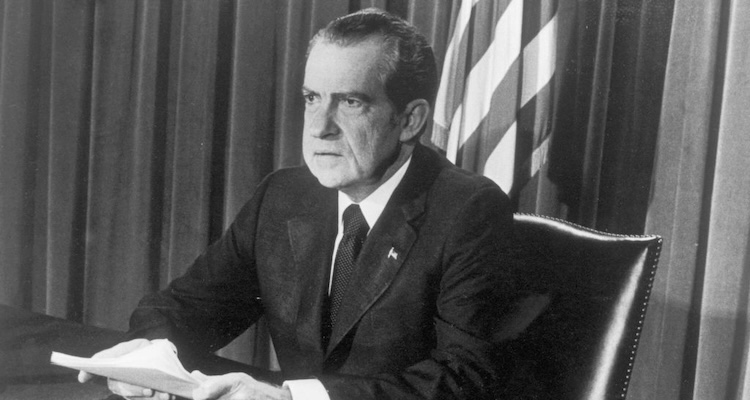

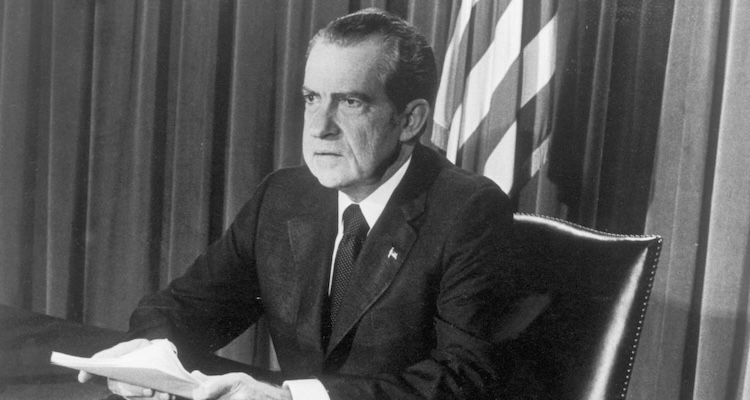

But Podhoretz had not yet joined forces with conservatives. The man who had defeated McGovern in a landslide, President Richard Nixon, was consumed by investigations into the Watergate break-in. As Nixon’s domestic stature weakened, so did America’s strength abroad. Deterrence failed. Enemies noticed.

Toward the end of Podhoretz’s trip, on Judaism’s holiest day, Egypt and Syria invaded Israel and launched the Yom Kippur War. Three days after that, Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned after pleading no contest to tax evasion. The nation and world were caught between a Democratic Party in an anti-American fervor, and a Republican Party reeling from scandal. Pessimism reigned.

Hence Podhoretz’s lecture title: “Is America Falling Apart?” His answer was contrarian. Not only was America holding together, he argued, in some ways it was also stronger than before. The American people weren’t responsible for inflation, protest, and Watergate, he said. America’s elites were. Liberals had lost their identity and no longer knew what they stood for. And conservatives had lost their self-confidence—their sense of morality, their identification with law and order. Neither side was able to lead.

Once, Podhoretz said, liberals had championed economic growth, internationalism, and racial integration. By the ’70s, however, liberalism had abandoned all these positions. Pro-growth economic policy had been replaced by environmentalism and consumer protection. Interventionist foreign policy had warped into the neo-isolationism of McGovern’s “Come Home, America” campaign slogan. The idea of color blindness and the dream of integration had been delegitimized by affirmative action, riots, assassinations, and crime.

Nixon Republicans, meanwhile, presented themselves as responsible leaders who could navigate the turbulent waters of Vietnam and domestic unrest. And Nixon had been successful in withdrawing U.S. troops from Vietnam and in reaching an accord with the Communist North Vietnamese. But his involvement in Watergate stained the reputation of both his administration and the GOP. Nixon embraced the methods of one of his heroes, former French President Charles de Gaulle—heavy-handed executive orders and intrusive central government. It worked better in the original French.

Yet America endured. The paradox of Watergate, Podhoretz said, was that it strengthened U.S. institutions by reminding Americans of their ability to restrain arbitrary power. Podhoretz also took solace in the fact that the American people were richer, better educated, and more tolerant of ethnic, religious, racial, and sexual difference than before. They were proud of their free society—“the kind of society,” Podhoretz wrote, “that used to be called a bourgeois democracy.”

The nation was in crisis because liberal and conservative elites had, for different reasons, lost their faith in bourgeois democracy and in the public. McGovern’s new liberalism sought to swap America’s institutions for socialist bureaucracy. Nixon’s Gaullism, in pursuit of stability, evaded or violated constitutional guardrails. Both parties ran afoul of the traditional values and habits and common sense of the American people. Chaos was the result.

But it wouldn’t last. Podhoretz ended on a hopeful note. The collapse of American leadership, he said, “is a necessary precondition to the development of a governing elite which, as is proper to the workings of a truly democratic society, follows as much as it leads, and leads precisely out of its superior capacity to articulate and make coherent what the people feel and think and want.” Indeed, by the end of the decade, voters had taken the first steps toward better governance. They inaugurated a new political era. The nation avoided Podhoretz’s worst fears of Communist victory and American decline.

Will we be so lucky? It’s impossible to read Podhoretz’s address without seeing parallels between 1973 and 2025. George McGovern’s new liberalism has reappeared, with a sharpened anti-Semitic edge, in Zohran Mamdani’s democratic socialism. Nixon’s Gaullism struts across the Ultimate Fighting Championship stage, fashionably dressed, in the figure of Donald Trump. Russia murders Ukrainian civilians and menaces Europe. Radical Islam’s war against Israel and the West inspires a global wave of violent anti-Semitism. Communist China was still recovering from the Cultural Revolution when Podhoretz traveled to Asia. Now it’s a global superpower with designs on democratic Taiwan.

At home, Americans distrust their institutions. The rising generation devalues patriotism. It’s suspicious of the American dream, of upward mobility, of family and faith. The American people, too, seem coarser than they were half a century ago—more given to public displays of vulgarity, lewdness, rudeness, and random violence. For every similarity between the early ’70s and now, there is a postmodern twist—social media, podcasts, AI, Covid, mass immigration, transgenderism—that makes the current situation stranger and more menacing.

And yet, buried under layers of luxury and self-doubt, America’s political and economic institutions still hum with energy. Most Americans still exhibit the bourgeois democratic values that have sustained the nation on its journey to greatness. If our current political leadership doesn’t seem quite up to the task of both articulating and executing popular desires, a new generation is waiting in the wings. These new leaders will have personal and political faults of their own, of course. Leaders always do. But they may also be better suited for the task ahead. Better equipped to defend what’s best in America.

The exceptional nature of this country’s founding, its connection to the greatest glories of Judaism and Christianity and Western civilization, endows it with remarkable recuperative powers that are continually at work. That is why Norman Podhoretz was able to conclude that America was in better shape than it looked. Commentary exists to remind Americans of this noble inheritance. Commentary is here to rebuke those intellectuals and politicians so eager to defame and demean the values, systems, and policies that promote freedom and prosperity. Eight decades later, the job isn’t finished. It never is.

Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.