President Teddy Roosevelt couldn’t make it to the Hanukkah party. He sent his regrets. But in his December 17, 1908, reply to Rabbi Stephen S. Wise’s invitation, Roosevelt expressed his admiration for the ancient Hebrew heroes whose legendary defeat of the Seleucid-Greeks served as inspiration for the Festival of Lights. “I wish I could be present in view of the fact that it is to take the form of a Maccabean festival, for as you know the fine loyalty and valiant achievement of the Maccabees have always made them favorite heroes of mine,” Roosevelt wrote. “It is a good thing that the Jewish boys and girls should keep their pride for and admiration for their own heroes of early days, and such pride and admiration, instead of hindering them, will help them to the friendliest and most brotherly relations with their fellow Americans.”

As Andrew Porwancher details in his engaging and informative American Maccabee: Theodore Roosevelt and the Jews, those Israelite fighters of millennia ago often shaped how Roosevelt viewed the Jews of his own time. (Porwancher, who teaches at Arizona State University, is the author of a previous work collating evidence that Alexander Hamilton came from a Jewish background.)

Roosevelt’s philo-Semitism was unlikely, given his background. A “silver-spooned statesman,” Roosevelt was “the ultimate insider of the Protestant elite that had long dominated American life,” writes Porwancher. “His father descended from a wealthy family whose eminence in Manhattan dated back generations. His mother was a Southern belle from Georgia whose lineage included a delegate to the Continental Congress.” His upbringing couldn’t have contrasted more sharply with the Yiddish-speaking immigrants toiling in Manhattan’s Lower East Side sweatshops with whom he interacted as New York City’s police commissioner in the mid-1890s.

Yet even as a youth, he spoke out against Jew-hatred. Shortly after his college graduation, Roosevelt rebuked fellow members of a Republican club who wanted to reject a Jewish applicant because of his faith. And after hosting a novelist for an afternoon at the Harvard Club, he noticed that the writer’s story featured a Jewish antagonist but exclusively Gentile protagonists. “There ought also to be a Jew among them!” Roosevelt declared. It must be said, though, that his record was hardly perfect. He would later describe a Jewish journalist as a “circumcised skunk” and, in a letter to a friend, refer to a Jewish politician as a “sheeny” (a now-unfamiliar anti-Semitic slur).

As commissioner, Roosevelt, who had developed a lifelong commitment to physical fitness after a sickly childhood, wrote an essay detailing how “few people have any idea” of the large number of Jewish policemen he had hired. “The great bulk of the Jewish population, especially the immigrants from Russia and Poland, are of weak physique and have not yet gotten far enough away from their centuries of oppression and degradation to make good policemen,” he wrote. But “the outdoor Jew who has been a gripman, or the driver of an express-wagon, or a guard on the Elevated [train], or the indoor Jew of fine bodily powers who has taken to boxing, wrestling and the like, offers excellent material for the force.” Therefore, he wrote, “I made up my mind, it would be a particularly good thing for men of the Jewish race to develop that side of them which I might call the Maccabee or fighting Jewish type.”

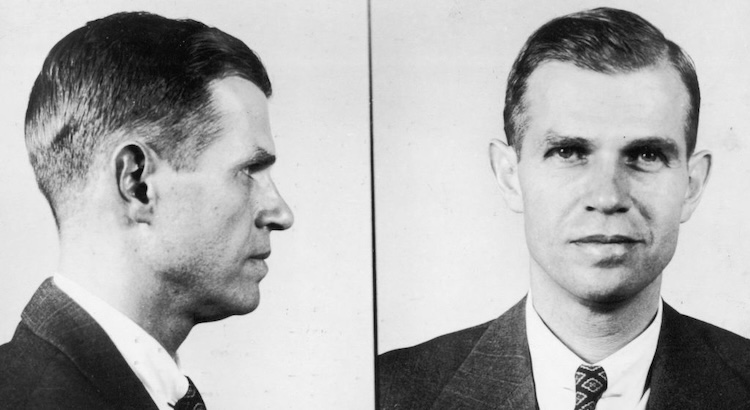

One such man, Otto Raphael, was personally recruited by Roosevelt after being introduced to him at a local YMCA event. Raphael, a Russian immigrant, had recently rescued multiple people from a burning building. Roosevelt thought Raphael “a powerful fellow, with [a] good-humored intelligent face.” The two became sparring partners and lifelong friends. Roosevelt would visit with Raphael’s family, and Raphael would later visit the president at the White House. In his autobiography, Roosevelt would write affectionately about how he and Raphael “were both ‘straight New York’ to use the vernacular of our native city.”

For these Lower East Siders, Porwancher emphasizes, “the sight of a fellow Jew sporting a police uniform was a stirring symbol of American possibility. Policemen back in Russia enforced discriminatory laws against Jews, and during the outbreak of pogroms, they had passively watched as mobs mercilessly beat Jewish victims.”

When, in 1895, the German anti-Semitic preacher Hermann Ahlwardt came to town to deliver a speech that happened to fall on Hanukkah, Commissioner Roosevelt purposely surrounded him with an all-Jewish police detail, displaying the American values of free speech and religious liberty. An observer of the Jewish officers that evening quipped, “a more Hebraic group of Hebrews probably never were gathered.”

_____________

Three years later, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders fought in the Spanish-American War, which, the author notes, “the Jewish press depicted…in Biblical terms by analogizing the Spanish king to Pharaoh, the Caribbean Sea to the Red Sea, and the American troops to the Chosen People.” Under Roosevelt’s command were multiple Jewish soldiers, and San Francisco’s Jewish newspaper would note that these “volunteers fight not as Jews, but as Americans who love and honor the flag that rouses the Maccabean blood in them.”

As president, Roosevelt made a dramatic visit to Ellis Island harbor to announce a special committee—with Jewish representation—that would expose prejudicial practices in immigration processing. When a Jewish college student published an article endorsing his reelection in a monthly magazine called Menorah, the commander in chief gushed about the essay to a friend. He even intervened to ensure that the Republicans had an Orthodox Jew on the slate of judicial nominees for the city bench back in New York. He was the first president to nominate a Jewish cabinet member—Oscar Straus—as secretary of commerce and labor. And in a letter Roosevelt composed to be read aloud in Carnegie Hall at an event celebrating 250 years of Jewish life in America, he wrote: “While the Jews of the United States… have remained loyal to their faith and their race traditions, they have become indissolubly incorporated in the great army of American citizenship.” When an American comedian jokingly spelled his name in a Judaized way—Tiddy Rosenfelt—Roosevelt responded, “I wish I had a Little Jew in me.”

Roosevelt’s personal affinity for many Jews didn’t always translate into policy. He could have spoken out more strongly against Russia’s persecution of its Jews and allowed more Jewish immigration into the United States. He also embraced the themes of Israel Zangwill’s The Melting Pot, the theatrical sensation of 1908, which alienated many Jews because it explicitly advocated Jewish assimilation into the larger American polis. Porwancher says there were two Theodore Roosevelts: “One inspired his Jewish constituents; the other disappointed them. One spoke up for persecuted Jews overseas; the other kept a studied silence. One roundly repudiated Jew-hatred; the other indulged in antisemitic tropes. One warmly embraced Jewish immigrants; the other sought to limit their admission.”

Yet upon the former president’s passing, as he lay in his home awaiting burial, Porwancher notes, “only one person was permitted to keep vigil over the body.” He goes on: “That honor didn’t fall to any of the famous personages who had populated his life, nor to the best man at his wedding, nor even to his eldest child. In these small hours, as the world slept, Roosevelt’s sole companion was a Russian-Jewish immigrant: Otto Raphael…. On that last evening in Sagamore Hill, amid a trophy room adorned with the tokens of feats and fame, there could be no finer symbol of the very best in Roosevelt than this final farewell between two faithful friends.”

Photo: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.