As it would say in a Haggadah of American life: “In every generation, we will tell the story of Marty Glickman.” At the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Glickman was a member of the U.S. track team and was prevented from competing so as not to confront Hitler with the image of a Jew winning gold. Do you see the empty chair at the table? It awaits the return of the Brooklyn boy who, having died in 2001, is probably running hurdles in heaven. The Elijah cup might be filled with Dr. Brown’s Cream Soda or an egg cream. He could share it with Marty, whose story we should tell before every Olympics, as it encapsulates the promise and the pain, the sugar and the diabetes, of Jewish life in America.

He began as a 1930s playground legend in Flatbush, when Brooklyn was a capital of sports, a republic of kids aswarm on vacant lots, the stoops and alleyways where every game—stickball, stoopball, punchball, Johnny on the Pony—became a twilight battle. Marty’s gift was speed. Onlookers guffawed as they watched him race his father, a cotton-goods salesman from Romania, down the beach at Coney Island. He excelled at basketball when many of the game’s great stars were Jewish, a fact that was often attributed to the craftiness—the Yiddishe kop—of the Jew. Typical of the time: a 1936 Daily News column that claimed basketball “appeals to the Hebrew [because it] places a premium on an alert, scheming mind and flashy trickiness, artful dodging and general smart-alecness.” In this way, in America before the war, even your excellence was used to defame your character.

He made his first newspaper appearance on October 13, 1934. The article, which topped the Brooklyn Daily Eagle sports section under the headline “Marty Glickman leads Madison Wrecking Crew in Fall of Erasmus,” was a chapter in a great Brooklyn sporting rivalry: Madison versus Erasmus in the game of football—which, in the mid-1930s, meant Glickman vs. Luckman. Since the quarterback position as we now know it would not be invented for another decade by Erasmus Hall’s Sid Luckman on the Chicago Bears, the 1934 public-school championship was a battle of tailbacks, Marty and Sid operating out of the old single wing, taking the snap, racing along the line, looking for a hole in the defense.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle led with Marty, “a smiling kid in slick silken football pants,” accompanied by a photo that is like an image from a gridiron dream—muddy faces beneath leather helmets, high-top cleats, the ball carried by young Sid Luckman (whose father Meyer, an associate of the Jewish mob Murder Incorporated, would die in Sing Sing). Sid was brutish, handsome but dinged, as dented as a getaway car. Marty was almost cute by comparison, compact and boyish, like a kid you remember from summer camp.

Marty, who played safety on defense, intercepted Sid in the second quarter and took the ball 75 yards for the touchdown that clinched it. Played at Ebbets Field in front of 20,000 people, that game linked Glickman and Luckman in the minds of a generation of Brooklyn Jews—Sid, who would go pro and lead the Bears to four NFL championships, Marty who would go to Berlin and sit.

_____________

Glickman was a college freshman when he made the Olympic track-and-field team in 1936. Archie Williams, Glenn Hardin, Jesse Owens, Ralph Metcalfe—that was arguably the best squad America ever assembled. Mack Robinson, Jackie’s brother, ran the 200 meters. Marty, already a Syracuse University football star, was one of two Jews. The other was Sam Stoller from the University of Michigan, who, in the saga of the 36 Olympics, is like Enoch in the Bible. His presence at the games, noted but never canonized, is the provenance of completists. For while Glickman would talk and talk about what happened, Stoller was forever shamed into silence.

The Berlin games were all about Hitler. The main events were held in the German capital at the height of Nazi power. The contests were seen by Nazi leaders as an occasion to demonstrate the superiority of the Aryan. Some blacks and Jews called for a boycott. To others, it seemed like an opportunity to expose the lie of Nazi ideology.

The Olympic Stadium, built specially for the games, remains a landmark in Berlin. Glickman, then just 18, found the vast horseshoe-shaped arena “particularly impressive when filled with 120,000 people.” He said later that “when Hitler walked into the Stadium, the stands would rise, and you’d hear it in unison, ‘Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil,’ all together, this huge sound reverberating. Everyone seemed to be in uniform. As for banners and flags, they were all over the place, dominated by the swastika.”

The U.S. track team’s performance was historic: 25 medals, 14 gold. Jesse Owens, who set several world records, was the exact sort of star Hitler did not want. Superior to all challengers, Owens annihilated the German Übermenschen, as if he were operating at a different speed, in a different kind of vehicle. The Führer watched from the grandstand in the manner of a Roman Caesar, surrounded by sycophants, sometimes laughing, sometimes turning away in disgust.

Stoller and Glickman were supposed to run the first and second legs of the 400-meter relay on August 9, 1936. They spent weeks practicing the baton hand-off, because that’s where nerves can get you. The night before the race, the entire team was called together by Avery Brundage, the president of the U.S. Olympic Committee, and Dean Cromwell, the team’s assistant coach.

This meeting is a diorama in the memory palace of the American Jews. Brundage—whom history has made a villain because he was a villain—had been a member of the 1912 Olympic team. He’d competed in events dominated by Jim Thorpe, the Native American athlete who, in a terrific act of historical injustice, was stripped of his gold medals for violating a policy on amateurism. Thorpe had taken a few dollars—food money, mostly—to play in a summer baseball league during college. Later, as the head of the U.S. Olympic Committee, Brundage blocked the return of Thorpe’s medals for decades.

And it was Brundage who told Glickman and Stoller they would not race. Their spots in the relay would be taken by Owens and Metcalfe. This was the only time that members of the U.S. Olympic team traveled but did not compete. Asked to explain, Brundage cited a rumor that had Germany holding back two of their best sprinters so they could snatch the gold away from America.

“Sam was completely stunned,” Glickman said. “He didn’t say a word in the meeting. I was a brash 18-year-old kid, and I said ‘Coach, you can’t hide world-class sprinters.’ At which point, Jesse spoke up and said ‘Coach, I’ve won my 3 gold medals. I’m tired. I’ve had it. Let Marty and Sam run, they deserve it.’ [Coach] Cromwell pointed his finger at [Jesse] and said, ‘You’ll do as you’re told.’”

A perfect blue afternoon before the war, flags and swastikas, the chants of German masses, the ancient nations of Europe when the Old World was still intact. Glickman could see Hitler a hundred feet away in his box. He watched him during the relay. He wanted to see how he was taking it. When you close your eyes, you can almost picture the day as it should have unfolded. Glickman takes the baton from Stoller, kicks into a sprint, and is gone, the German supermen trying to keep pace smearing into a blur of color. Marty and Sam winning the gold medal would have changed nothing, of course, but it could have been a solace for a lot of Jews in the 1940s, an example of what we can do when we are allowed to compete. It instead became another instance of exclusion. The Jew is defamed not because they think he can’t keep up but because they know he can.

Brundage spoke at the pro-Nazi Bundist rally held at Madison Square Garden on February 20, 1939. And he would reappear in Germany in 1972, in his final act of monstrousness.

_____________

Marty Glickman’s revenge would have to come in the world brought into existence by Germany’s defeat. Pax-Americana. Disneyland and the Super Bowl. The long economic boom and resulting birth of our modern leisure culture. The sports book in Vegas. All the channels on TV.

He landed a broadcasting job while still playing football for Syracuse, making him one of the first to execute the ascent from field to booth. As all Russian literature is said to have come out of Gogol’s overcoat, all modern play-by-play and color commentary can be said to have come out of Marty’s vocal cords.

He got the first job on a hunch. After seeing him score two touchdowns to lead Syracuse in an upset of Cornell, the owner of a local men’s store offered Marty 15 bucks to talk sports on the radio. From there (credit his prodigious powers of description), he climbed gig to gig, until, by the 1960s, he’d become the voice of the Knicks and the football Giants. He did Yankee games, Dodger games, Jets games, locker-room interviews. There was also pro wrestling from the Garden, roller derbies, and rodeos. Or you might find him at Yonkers Raceway spitting out the syncopated rap of the horse-race announcer.

People loved his accent and the fact that he did not try to smooth the rough edges. It was authentic Flatbush, where they said “turlett” for toilet. It was the voice of the street corner, friends playing punchball as the sun went down. Now and then, because nothing else could really make the point, he’d drop in some Yiddishism—shtarker, meshuga, kvetch—counting on the goyim in TV Land to make sense by context. He was one of the secret agents who smuggled the language and culture of our grandparents into the mainstream.

The two strands of his career—on the field, and off—came together during the Munich Olympics in 1972. He’d been on the sideline 36 years earlier when the stadium was aswarm with Nazis and history singled out Marty and Sam—lit as if by spotlight, stamped verboten, marked as different than everyone else on the team; the loneliness must be emphasized—and here he was, watching a feed from the same country 36 years later as members of the Palestinian terrorist Black September murdered two Israeli athletes in the Olympic village and took nine others hostage, all of them killed during West Germany’s failed rescue attempt. It was as if everything in the world had changed except the predicament of the Jew.

The suggestion of postponing or canceling the games to acknowledge the terrible historical resonance—the Munich killings happened 10 miles from Dachau—was nixed by the organizers. They included the president of the International Olympic Committee, who said, “The games must go on.” His name: Avery Brundage.

I interviewed Marty Glickman in 1997. I was researching my book Tough Jews. I wanted to talk to him about the Jewish gangsters who lived in Brooklyn when he was growing up. He insisted that we meet at the Harmonie Club on East 60th Street in Manhattan, which had been founded by German Jews who’d been denied admittance to every other club in New York City. Marty, still boyish at 79, said he was making a point by meeting me there. “Right after we got back in 1936, a few weeks after Sam and I had not been allowed to race, a friend took me to the New York Athletic Club to work out,” Glickman said. “I was out on the track, stretching, when this man comes over and tells me I have to leave. Because the club was restricted. No blacks. No Jews.”

When I started working on this article, I wondered if it needed a peg, some event in the news that would demonstrate its relevance to our current lives. Maybe it could be timed to the start of the NBA season—for, as the voice of the Knicks, Marty innovated the use of the word “swish” to describe a ball that entered the basketball net without touching the rim. Or maybe it could be pegged to the preparations for the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles. Then I realized that it doesn’t need a peg because it already has one, and it is evergreen. If you don’t think what happened to Glickman and Stoller in Berlin can happen and is happening again—a Jew being told not to show up because his presence as a Jew would be offensive to some führer or mob—then you have not been paying attention.

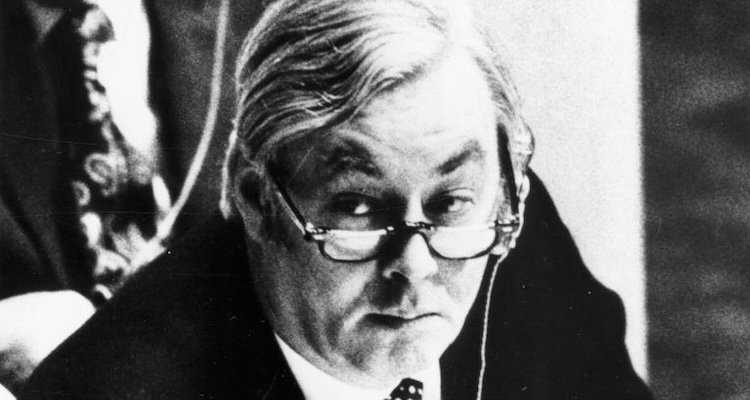

Film still from Glickman (2013), © HBO/Warner Archive. All rights reserved.

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.