On a September day in Utah, Charlie Kirk stood before an audience of students and supporters at Utah Valley University. By all accounts, he was doing what he had done countless times before—speaking with the urgency of a man whose vocation was persuasion. Then, in a single instant, the ordinary rhythm of a campus event gave way to chaos. A crack rang out; Kirk collapsed, struck in the neck. Witnesses screamed, fled, tried in vain to help. Hours later, the news confirmed what many had already feared: Charlie Kirk, husband and father, was dead. He was 31 years old.

In that moment, a movement defined by words faced its most terrible question: When speech is met with blood, can persuasion endure, or must fury give way to rage, radicalism, and resentment?

It was a moment that should never have happened; and yet, in the poisoned air of our age, we had all been waiting for it. Not to Kirk in particular—his death was a shock, sudden and cruel—but the act itself. The public killing of a man for what he believed was something any conservative could have foreseen, just as surely as many on the left would find a way to blame the right. Beneath the noise of politics, something older had been stirring—a moral hunger twisted to evil but disguised as virtue, waiting for permission to feed.

For years the hungry ghost of politics had been stirring beneath the surface—feeding on grievance, fattening on vanity—as it has always done before an age of ruin. Before the gulags, there were the denunciations; before the killing fields, the reeducation campaigns; before the Red Guards, the struggle sessions. The ritual is always the same: Speech is punished, doubt condemned, and posturing turned into a weapon. Out of that ritual rises something more dangerous still—a formless, amorphous rage that mistakes destruction for renewal, cruelty for courage, and outrage for truth.

Its power lies in its vagueness. It condemns not deeds but categories so vast that they seem to mean nothing at all, yet they are so elastic they can implicate nearly everyone. The Soviet Union called its enemies bourgeois; the Maoists called them counterrevolutionaries; the Khmer Rouge called them intellectuals. In our day, the press and its allies have renamed them “whiteness,” “the patriarchy,” and “the system.” The language changes, but the appetite does not. Its outline was visible in the thrill of denunciation, in the easy cruelty dressed as care—but those same voices pretended it was not there. They called this hunger compassion, its silence progress, its cruelty accountability. They insisted there was no such thing as “woke”; rather it was justice, speaking truth to power, a means of creating accountability. And so they blinded themselves to what they had summoned, even as it feasted before their eyes.

The hungry ghost never comes unannounced, to those who are brave enough to look for it.

The signs of its presence were everywhere, written not in manifestos but in daily humiliations, throughout the 2010s. It was the teacher marched off campus while students cheered his downfall, condemned not for a crime but for a phrase torn from context. It was the student who raised a question and was met not with argument but accusation, who learned that silence was the only safe opinion. It was the novelist watching her career collapse in real time, denounced by thousands who never opened her book, while publishers scrambled to erase her name. These were not distant horrors. They were small, ordinary crucifixions—and they marked the hungry ghost feeding on American life.

The same instincts that exiled teachers and ruined novelists soon found a larger stage. The dominant culture turned private intolerance into public ritual, magnifying grievance, manufacturing guilt, and calling the contagion justice. What had begun as cultural fashion hardened into civic faith, and the fever that once ruled campuses and screens was about to consume the nation itself.

When George Floyd died in Minneapolis in June 2020, the dominating culture rushed not to caution but to condemnation. Within hours, a single death was transformed into cosmic indictment. The presumed guilt of one man became proof of a nation’s original sin. No evidence was required. Not even the prosecution of Derek Chauvin, the cop who had held Floyd down while he died, claimed that racism had caused Floyd’s death, yet the nation was told to atone as though it had. From that leap—from the assumed guilt of an individual to the collective damnation of millions—followed everything else. Honest grief curdled into generalized fury. Cities burned, neighbors were turned into enemies, and destruction was mistaken for justice. The narrative was never rational but sacramental: America was to be purified not through reform but through fire. The nation was condemned wholesale before the facts had even been examined. And once that reflex took hold—the habit of moral certainty without evidence—it could not stop. It hardened into instinct: to see what confirmed the creed as truth, and what contradicted it as heresy.

When Charlie Kirk was murdered, that same moral reflex did not falter. It adapted. The instinct that had once turned tragedy into collective guilt now sought to make Kirk’s death the proof that it had been right all along. The same voices that preached repentance after Floyd’s death now implied or stated outright that conservatives themselves had been to blame—that the violence they suffered was merely the harvest of their own hate. Within days, Jimmy Kimmel suggested that the murderer was part of the right, the claim delivered not as irony but as revelation, within the easy moral theater of late-night television where outrage passes for insight. Meanwhile, a young widow clutched two children—a daughter of three, old enough to keep asking when her daddy was coming home, and a baby boy of one, too young ever to remember his father’s loving gaze. Their grief was met not with solemnity but with levity on national television. For the millions persuaded by the likes of Kimmel, Kirk’s death became not a tragedy but a vindication—another sacrament in the same faith that treats every conservative sin as proof of evil, and every conservative wound as evidence that evil deserved its pain.

Soon the hungry ghost found another voice. On Piers Morgan Uncensored, the YouTuber who calls himself Destiny argued that responsibility for Kirk’s murder lay not with the assassin, or the ideology that shaped him, but with Donald Trump and the right as a whole—blaming the only side that had not burned cities or stormed courthouses. It was a familiar inversion: the habit of blaming the victims for provoking their own destruction. It was the same chorus that nodded when Kamala Harris urged donations to bail out rioters in 2020 and described the fires that consumed neighborhoods as “mostly peaceful.”

This is the ideological permission structure for political violence—a moral calculus in which the righteousness of the cause sanctifies the cruelty of the act. Its adherents insist, “I denounce violence, but…” And in that hesitation lies the tacit blessing. Violence becomes deplorable in theory, inevitable in practice—not because it is judged just, but because it is blamed on those who provoke it merely by existing outside the creed. In this logic, every act of left-wing violence is a reaction, every act of right-wing speech a cause. It teaches that violence is tolerable if it advances the narrative, excusable if it serves the faith.

Then came the turn. As leaks began to suggest that the killer had been steeped in radical left-wing ideology, the national press and its allies abruptly changed tone. The certainty of moral judgment gave way to the performance of restraint. Commentators who had once thundered with righteousness now urged the public to wait for the facts—a caution they had never shown when the facts had been theirs to shape. Networks that had once seen hate everywhere suddenly saw nuance; pundits who had called silence violence now found it convenient to be silent. What had been systemic was now treated as exceptional. What had once been evil became, in their telling, inexplicable. This was an ambiguity born not of doubt but of fear: fear that their own recklessness had gone too far, that the fury they had nursed on the left might now conjure its equal and opposite on the right.

One of the voices who answered the hypocritical left-wing turn toward calculated prudence was Matt Walsh of the Daily Wire, a cultural polemicist unflinching in his attacks on progressive dogma. In the aftermath of Kirk’s murder, his fury gave voice to millions who felt their outrage mocked or erased. “I could never unite with the left and its allies,” he declared. “They want me dead. They would spit on my grave and laugh in the faces of my wife and children.” His words were raw, visceral, and, in part, righteous. They captured the exhaustion of a movement that has endured years of scorn without striking back—and the moment when the incantations of the national press and its allies stopped working their silencing magic.

The strategy that once choked the voice out of the opposition has begun to devour its authors. To wield moral panic as power is to spend legitimacy faster than it can be replenished, and they have squandered theirs. Their moral theater now convinces only the most faithful. It no longer frightens conservatives, who have learned that the threats of their enemies have become hollow; nor does it sway the undecided, who have begun to see the cruelty beneath the mask of virtue. The dishonesty that once compelled submission now provokes disgust. The charm has broken; the spell is spent.

_____________

For the right, this is both an opportunity—and a warning.

The right may now choose to embody the sanity it once defended—to hold fast to composure, to principle, to persuasion. Or it can inhale the very poison it has opposed. The temptation is strong to strike back, to cancel back, to bully back, to summon the same amorphous rage that consumed its foes. But to do so would be to repeat defeat in a different key—to declare liberal democracy itself irredeemable, to baptize vengeance as virtue, and to inherit not the mantle of justice but the ghosts of the Bolsheviks and Maoists whose tradition their enemies have been heir to for a decade or more. They too once dreamed of cleansing the world and instead drowned it in blood.

Fury, however justified, is perilous when it collapses into generality. In Walsh’s fury, many heard not grief but permission—to brand half the country complicit, to answer pain with contempt. That is how it begins, with the wound to one man swelling into hatred of millions. Those who take that step descend the staircase of temptation into amorphous rage—against “whiteness,” “the patriarchy,” “the left,” “the Democrats”—until abstraction hardens into something concrete, something that can be struck. The neighbor becomes the symbol, the man across the street the effigy.

Walsh is not a radical; his gift has always been to expose radicalism where it festers, as in his documentary called What Is a Woman? That is what makes Walsh’s fury so dangerous now—not because his intent is malign, but because grief spoken without restraint is always heard by someone else as license.

And so, if we are honest, we must ask ourselves: Do we on the right have the bravery to see whether the hungry ghost now walks among our own ranks, too?

Here the choice must be made plain. Anger at evil is not only permissible but necessary; without it, conservatism decays into passivity. But anger must be tempered into indignation—anchored to truth, disciplined by stewardship—lest it dissolve into amorphous rage. Righteous indignation steels a people to endure; amorphous anger corrodes them from within. It is the difference between Churchill’s fury at Nazism, sharpened into defiance that saved Britain, and the Jacobins’ rage at “the aristocracy,” incarnadine seething at a formless enemy, a seething that ended up devouring France itself. To collapse indignation into such rage is to mistake the fire that preserves for the fire that consumes.

That same confusion now tempts a new breed of openly reactionary intellectuals. Just like the radical left directing its fury against “the system,” the post-liberal right believes that the Enlightenment experiment at self-rule has failed. In their vision, liberal democracy itself has become the problem: an exhausted vessel, corrupt in essence, destined to fall. They do not call for violence. Like Marx, they simply declare the collapse inevitable. But it is that claim—the quiet assertion that the existing order is already dead—that invites chaos yet to come. Into that void, history always sends its zealots. Marx did not name his victims, yet Lenin and Stalin found them. Abstractions—“the bourgeois,” “the kulak,” “the counterrevolutionary”—became people, and people became corpses.

Unlike Walsh, who speaks in the voice of grief, Yoram Hazony and Patrick Deneen speak in the voice of theory. One is the architect of “National Conservatism”; the other, the author of Why Liberalism Failed and Regime Change. They command conferences, journals, and lecture halls where conservatism’s future is debated. Their tones are calm, their words respectable, but their conclusion is revolutionary: The liberal order itself is hollow, irredeemable, and must be replaced. With this, they step onto the same perilous path they claim to oppose. They are not offering repair in the manner of Edmund Burke but its negation: not preservation but purification, not the Federalist Papers but the Communist Manifesto with the names reversed. They dream of moral renewal, but that dream begins where every tragedy begins—with the conviction that the inheritance must burn before it can be redeemed.

The consequence can already be seen in Britain. Carl Benjamin, once a liberal critic of extremism, rose to prominence online as “Sargon of Akkad,” defending ordinary values against both the woke left and the alt-right. For a time, he proved that one could resist excess without succumbing to it. His anger was not misplaced: He saw clearly the cowardice of those who excused Islamist intolerance in the name of multiculturalism, and his indignation was the natural response of a man who loved his country and feared for its moral spine. But in time his indignation lost its shape. The righteous fury that once sought to defend the liberal order hardened into rage against the order itself. “The problem with the woke left wasn’t the woke part, it was the left part,” he declared—a phrase that revealed not opposition to fanaticism but rejection of liberal democracy itself. From there, his anger became identity; resentment supplanted liberty. The “other” was no longer merely the zealot who refused to integrate, but anyone who did not fit a narrowing vision of Englishness. So Benjamin claimed the flag belonged only to those of English blood, and that therefore Jews could never truly be English.

His fall is a tragedy—the loss of a steward who once held the line against extremism, only to join the ranks of those he opposed. His descent is a possible portent for a terrible turn on the American right. His journey shows how righteous anger can curdle into amorphous rage—when love of home turns into hatred of neighbor, when cultural inheritance is mistaken for ethnic possession, and when a people forgets that the truest test of belonging lies not in ancestry but in allegiance. If Benjamin could fall, any of us could—and if America abandons its inheritance, it could fall further still.

The American right has faced this temptation before. In the 1950s, McCarthyism turned a just fear of Soviet infiltration into a fever of suspicion. Professors, journalists, and public servants were accused of treachery not for what they had done, but for whom they knew. The fight against an enemy abroad became a purge against neighbors at home. At first it gave the right a surge of energy, but in the end it discredited conservatism itself for a generation—blurring the line between vigilance and paranoia, patriotism and persecution—and handed progressives a weapon they have wielded ever since.

Now, after Kirk’s murder, that same choice lies before us once more: whether to meet violence with stewardship or with vengeance; whether to conserve a civilization or to consume it.

Today, Anglo-American conservatism stands on a knife’s edge: on one side, the ordered tradition of Burke, Churchill, and Reagan; on the other, the amorphous chaos of grievance without providence. Some institutions have already fallen—the Heritage Foundation, once a guardian of principle, now a vessel for resentment; The Federalist website, which thrives on outrage more than order. Others waver: First Things, once a serious voice of religious conservatism, now tempted by integralist dreams; even parts of the evangelical movement, uncertain whether to preserve or to destroy. Yet some remain faithful—the Hudson Institute, National Review, the Free Press, and civic institutions that remember what conservatism truly is. But even the faithful must remain watchful and must speak out. The hungry ghost is not banished by silence; it grows in the dark, waiting until the moment it erupts. Institutions, like men, can be overtaken by that shadow if they mistake resentment for principle or mistake generalized vengeance for principled justice. When they do, they no longer preserve the inheritance but profane it—corroding the covenant they were entrusted to defend.

The temptation to meet radicalism with radicalism is not new. History offers a clearer lesson. Churchill and Reagan both understood that endurance, not escalation, defeats extremism: that when your adversary is destroying himself, the worst mistake is to join him in the flames. The same truth applies now. The national press and its allies are already consumed by the hysteria they unleashed, their moral authority collapsing beneath the weight of their own hypocrisy. The task of conservatives is not to mirror that collapse, but to outlast it—to hold fast to steadiness while the frenzy burns itself out.

Today’s left-wing radicals have attacked, murdered, and poisoned public life. Yet compared with the storms our grandparents weathered, their violence is a lesser gale. And if we meet it with the same discipline—gratitude for what we have, faith in who we are, endurance in what we defend—then we shall prevail as surely as they did. For the inheritance we hold is not a relic but a living covenant: written in liberty, guarded in patience, renewed in hope. It is the hearth our forebears kept alight through war and tyranny, the trust they placed in us not to squander in fury but to hand on, undiminished. Let radicals rage and consume themselves; our charge is steadier and more enduring.

At this hour conservatives must choose. Will we be stewards of a civilization—or spectators at its funeral pyre? Ours is not the rejection of anger, but its refinement—the transfiguration of grief into righteous indignation rather than its descent into amorphous rage. Indignation anchors itself to stewardship and memory; rage anchors itself to nothing and so consumes everything. If we confuse the two, we cease to conserve and begin to corrode. But if we make anger into covenant, it becomes a flame that steels without destroying—a fire that endures when rage has burned itself to ash.

The flame endures, if we do. But if we yield it to rage, it will not be civilization’s light that survives, but its ashes. That was the question left burning on the night Charlie Kirk fell—and it remains the question by which our civilization will stand or fall.

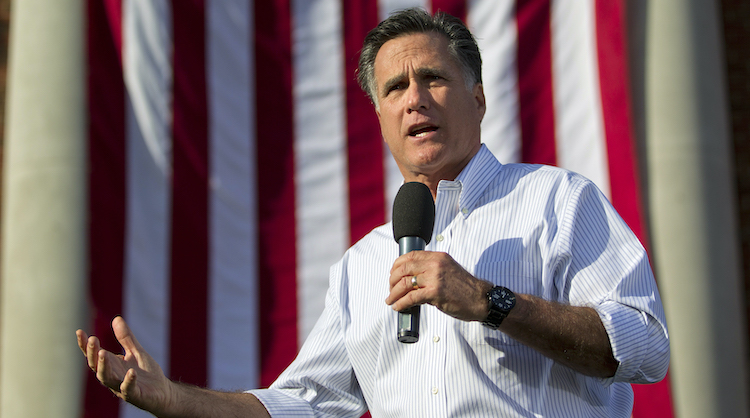

Photo: Mathieu Lewis-Rolland/Getty Images

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.