She was a genius; why not begin there? Muriel Spark’s 22 technically brilliant, subversively comic novels have earned her a sinecure in the literary canon. But, boy, those books are weird—startling, savage, bristling with betrayals, deceptions, and murder. Their creator, by general consensus, had a charismatic, if tricky, personality. The novelist Shirley Hazzard, a close friend until abruptly she was not, believed that Spark possessed second sight and recounted to Martin Stannard, Spark’s authorized biographer, how “things happened, odd things, when she was around.” The critic Frank Kermode recalled being advised by Spark not to cancel a party the day after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Why stop having pleasure because the president was dead? He was dead, she pronounced, only because God wanted him.

Spark has attracted biographic interest for over 60 years. When her estranged lover Derek Stanford published Muriel Spark: A Biographical and Critical Study in 1963, she was furious. Eager to “put the record straight,” she wrote a memoir. But she so much preferred examining her life through fiction rather than fact that Curriculum Vitae didn’t appear until 1992. The same year, she offered Stannard, a biographer of Evelyn Waugh and a professor of English at Leicester University, full access to her copious archives to produce an authorized life—only to fall out with him immediately upon reading a first draft of Muriel Spark: The Biography. Stannard’s thorough, if conventional, work was eventually published in 2009, three years after her death.

Now appears Frances Wilson’s Electric Spark: The Enigma of Dame Muriel, to be followed next year by James Bailey’s Like a Cat Loves a Bird: The Nine Lives of Muriel Spark (a title inspired by Spark’s own description of her feelings for her characters). Wilson, a biographer of D.H. Lawrence and Thomas De Quincey, references the Stannard-Spark conflict in her prologue and sets out a semi-corrective purpose. The novelist, Wilson says, “suffered from foresight, and this is the subject of Electric Spark”—an intriguing and suitably Sparkian declaration, but what exactly does it mean?

Wilson elaborates over nearly 400 pages, covering the dramatic encounters, painful deceptions, and strange happenstances of Spark’s first 39 years, culminating in the publication of The Comforters, her first novel. Spark insisted that those vivid events, along with her embrace of Catholicism in 1954, made her the artist she had believed, since her school days, that she was destined to become. “I haven’t got a message to give to the world, it’s the world that gives me messages,” Spark once said. Wilson endorses this self-assessment—which is both the strength and weakness of Electric Spark.

_____________

When Muriel Sarah Camberg was born on February 1, 1918, in Edinburgh, roughly 400 Jewish families lived in the city. Her father, Barney, employed by a rubber factory, was the son of an Orthodox couple who immigrated from Lithuania to Scotland in 1871. Her mother, Cissy, was born a Protestant in England, to a half-Jewish mother. Decades later, Spark argued with her son Robin over the extent of her mother’s Jewishness; he claimed that Cissy had converted, while Spark insisted that her mother had remained a Christian, making Muriel herself a “Gentile Jewess,” or “both and neither.”

The Camberg family of four (young Muriel had an older brother) lived in a two-bedroom flat and took in lodgers, so Spark slept on a sofa in the kitchen. Wilson does a commendable job describing the Edinburgh of Spark’s childhood, a noisy, crowded, commercial town, and her time at James Gillespie’s School for Girls, which Spark later immortalized as the Marcia Blaine School for Girls in her best-known novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. A scholarship student and academic star, she fell in love with poetry, both the classics and Scottish ballads, and wrote much verse herself. Wilson devotes inordinate space to retelling the tragedy of Mary Queen of Scots, “the first Catholic in Spark’s world,” because the queen obsessed Spark as a girl—long before she, too, was the spouse of a terrorizing husband, mother of an only son, and subject, by her own lights, of evil plots.

Spark married improvidently and hastily, at age 19, to a schoolteacher 13 years her senior named Sydney Oswald “Ossie” Spark. He promised a comfortable life in Rhodesia, where he’d been offered a new job. Spark herself could never properly account for this choice. Sheer willfulness? A desire for adventure? Eagerness to have sex and live independently? Her parents lacked money to send her to university, so she left behind only a secretarial job. Still, her folly was quickly apparent when, after she arrived in Africa, her husband began to wield a pistol in the house and show signs of violent paranoia. By that time, Spark was pregnant. She narrowly survived a bout of septicemia after delivering Robin and struggled on for a year before resolving late in 1939 to separate from Ossie.

She made her decision while staying at a Victoria Falls boarding house. By extraordinary coincidence, Nita McEwen—a young woman exactly Spark’s age and someone who resembled her physically, grew up around the corner in Edinburgh, and attended James Gillespie’s with her—was also a guest. “Having also married a mentally unstable man and come with him to Africa, Nita was shot during their visit by her husband, who then killed himself,” Wilson writes, repeating the version of events Spark provides in her memoir. But there’s no proof McEwen ever existed, as Wilson concedes, and she struggles to explain why Spark might have inserted a fictional doppelgänger into her life story (although she does note that “Nita McEwen” is an anagram for “Twin Menace”).

Wilson gallops through the next few years of the novelist’s life, a period during which she undertook a perilous wartime journey on a U-boat-dodging freighter, leaving Robin in Africa until she could transfer him to her parents’ care in 1945. Spark moved into the Helena Club, in Kensington, London, commemorated as the May of Teck Club in her splendid 1963 novel, The Girls of Slender Means. She found work with the Foreign Office producing black propaganda—“truth with believable lies” was the brief—to demoralize German civilians via radio shows and counterfeit newspaper articles. Hard to conceive of a stranger, or more potent, stand-in for a two-year MFA program than this.

In May 1947, she became the general secretary of the Poetry Society in London and, later that year, the editor of the Poetry Review. She immediately revitalized the publication—the previous editor had disdained the “morbid tendency” of contemporary poetry—but was brought down after six issues by the intriguing of jealous rivals in the society, among them a rebarbative Marie Stopes, writer and campaigner for eugenics and women’s rights. In Spark’s 1981 novel Loitering with Intent, she revisited her Poetry Society tenure and her joy (despite impecuniosity) of living a literary life in London. Her alter ego in that book, Fleur Talbot, says: “When people say that nothing happens in their lives, I believe them. But you must understand that everything happens to an artist; time is always redeemed, nothing is lost, and wonders never cease.”

_____________

The true source of wonder for Spark was, of course, God, and her conversion to Catholicism followed two unsatisfactory love affairs and a mental collapse, including hallucinations brought on by overuse of Dexedrine. Howard Sergeant, a married poet and editor whom Spark called Leslie because he looked like the film star Leslie Howard, made her generally miserable for 18 months. On the rebound from Sergeant, she took up with writer Derek Stanford in early 1949. “Muriel divided the world into angels and demons, and before he became a demon, Stanford was her seraph,” Wilson writes. Not only lovers, they also composed poetry together, co-authored books, and supported each other’s literary ventures, including Spark’s Child of Light—a 1951 well-received critical biography of Mary Shelley, the second famous Mary who obsessed her.

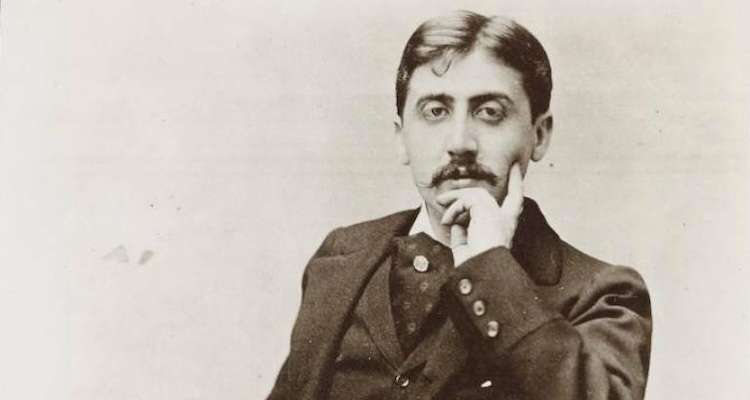

Stanford, later the blueprint for, in Wilson’s words, many of “Spark’s fakes, snoops, frauds, and literary failures,” desired to get married, but not to her, a divorced woman with a child. He also came to resent her superior talent. Spark recalled that after she won the Observer short-story contest in 1951 for “The Seraph and the Zambesi,” Stanford began to hate her. Yet they were still purportedly friends in 1955 when she retreated from London to work in peace in the Kent countryside. Stanford offered to pack up her flat and took the opportunity to purloin her youthful poetry notebooks and manuscripts of early stories. Seven years later, when Spark had achieved international renown for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, he sold these papers, along with Spark’s letters to him, to a dealer. The loss of the letters didn’t bother her greatly, but Spark hated that money raised by the sale of “notebooks of my young dreams…went to line the pockets of unscrupulous strangers.”

Accepting God’s dominion gave Spark a way of comprehending the world, with all its perfidy and erratic violence. Wilson, who is excellent on the influence of Mary Shelley and Elizabeth Bowen on Spark’s work, has more difficulty pinning down the Catholic spirit of her novels, perhaps because it is unique and shape-shifting. Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh—both Catholic converts admired by, and admiring of, Spark—constructed plots that are more obviously Catholic, concerning adultery, sin, and redemption, while Spark wrote, with dark humor, about oddballs and chicanery. The motivations of her characters are frequently obscure, and her stories follow enigmatic chains of causality. It has been said that Spark enjoys playing God in her novels. Wilson gets closer to the truth when she says the intention of Spark’s fiction is to demonstrate that God alone knows and understands human beings, who remain essentially unknowable to each other.

Electric Spark is an interesting read, but clinical—one doesn’t come away with a sense of having encountered a flesh-and-blood person. For that, Spark fans should turn to Alan Taylor’s engaging and admiring memoir, Appointment in Arezzo: A Friendship with Muriel Spark, published in 2018, to celebrate the centenary of her birth. The Gentile Jewess and Catholic convert always retained the Presbyterian ethic acquired in her Edinburgh youth, Taylor argues, writing of Spark’s worldview: “Life is what you make of it. What one achieved was by one’s own efforts. Take nothing for granted. Expect no favors—nor, for that matter, much in the way of thanks or praise.”

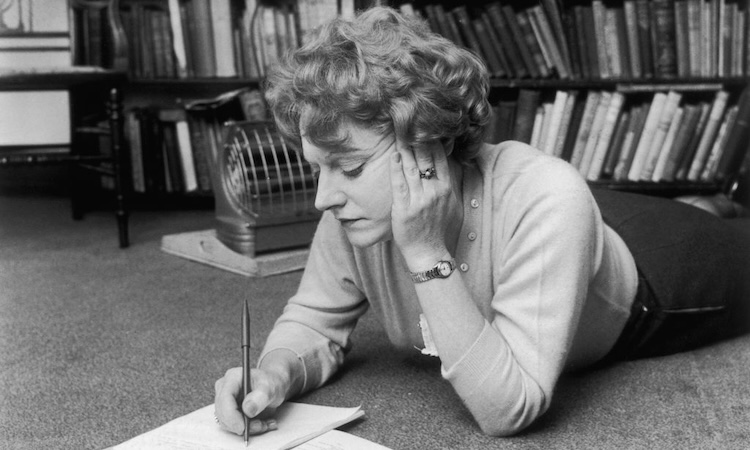

Photo: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.