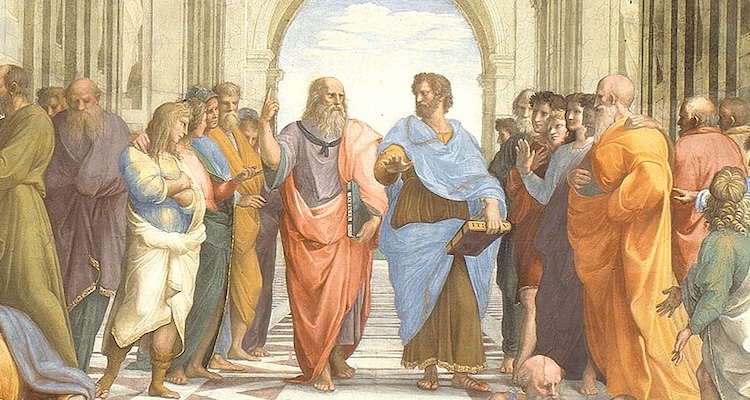

On the debit side of old age, perhaps none ranks higher than the death of friends. At 88, I easily qualify for old age, and in this past year or so have lost four good friends. I’ve lost friends to death before, but chiefly among them people older than I, some of them well-known in intellectual circles: the editor and critic John Gross, the novelist Dan Jacobson, the cultural critic Hilton Kramer. But, as Aristotle notes in the Nicomachean Ethics, “Two things that contribute greatly to friendship are a common upbringing and similarity of age.” The friends I lost this past year, all of them my contemporaries, male, heterosexual, Jewish, living nearby, were neither well-known nor, as the world recognizes such things, especially distinguished. I miss them, sorely.

Norm and I went back a mere 77 years, having first met when my family moved into his neighborhood of West Rogers Park in Chicago. He was a notably good athlete, less in organized sports than in nature. He could climb higher in trees than the rest of us, wrestle better; on his bike, a blue Schwinn racer, he was able to ride himself on his own handlebars. Later, in high school, he was the city champion at the stroke known as the butterfly. To the end of his life he worked out, doing chin-ups, sit-ups, one-hand push-ups. He kept a vanity car license plate that read “Stormin,” with the phrase “Stormin’ Norman” intended. If, at the gates of heaven, he were to be asked what he did while on earth, a truthful answer would have been “Stayed in shape.”

In a long life, Norm neglected to make any real money. Work was always a sideline for him. His last job, one he held for decades, was in an advertising agency devoted to employment ads. At the agency, Norm was the guy who arranged the brackets for betting on the annual NCAA basketball tournament. He organized and played first base on the agency softball team, which played against other ad agencies. He lived out his life in one of the two apartments in the same two-flat building in which he grew up. We lunched together regularly, and I noted he invariably ordered the least expensive items on the menu; in his last years, he took a pass on ordering coffee, which he enjoyed but which generally cost $3. He had, in other words, to be careful.

Family was important to Norm. He had two sisters, both younger than he, whom he loved, three children (two boys and a girl), and two grandchildren. Birthdays were grand occasions in the family, and he could be a touch aggrieved if any among his close friends neglected to call him on his (April 30). Birthdays called for family dinners, usually at restaurants, but sometimes at his apartment. He was a cook in the Army, during which he served what in those distant days of the draft was known as a “six-month deal.”

Norm married an Italian, Luciana, who had come to America with her sister Anna Maria to work for the Olivetti Company. They met as part of a group that partied during summers on Oak Street Beach, near downtown Chicago. After they married, Norm and she gave parties at their West Rogers Park apartment. That Norm, who had never been to Europe, married a woman from Rome seemed more than a touch exotic to him. Luciana, called Lu by all, was pretty when young, though she grew heavy and her good looks departed when she grew older. She died 10 or so years before he, who never took out another woman. He kept her ashes in an urn on the mantle of the never-used fireplace in his apartment.

Smart enough in the ways of the world, Norm had no interest in culture. So far as I know, he read few books and never attended a classical concert. After high school he went off to the University of Illinois on probation and flunked out after his first semester there. He continued on at Roosevelt University—Ru U, as it was then called—though I doubt if he acquired a degree there. I gave him signed copies of all my books, on which he rarely commented. He preferred information over knowledge, especially information about sports. He was a Democrat, without being in the least ideological. Being a Democrat was like being Jewish, something he was born into.

In our 77-year friendship we never had anything resembling a serious argument. Neither in all that time did we ever speak of things of the heart. He never told me, or even hinted at, the disappointments in his life, the mistaken moves he had made, his regrets. We mostly talked about old friends from grammar and high-school days, about our parents, about sports. Our friendship, lived chiefly on the surface, nevertheless survived the decades. Yet on that surface it somehow achieved depth. How else account for my missing him so today.

_____________

I first met Stan in college, at the University of Illinois, where he was a semester ahead of me, a so-called pre-dent student, and a member of Phi Epsilon Pi, the fraternity I had pledged. He was from Sioux City, Iowa, and why he came to Illinois instead of studying at Iowa I do not know. We were not especially close, though we liked each other straightaway. After finishing dental school, he opened a successful practice in Highland Park, the North Shore suburb heavily populated by upper-middle-class Jews. He married the daughter of a wealthy family living in what was then still the white and Jewish neighborhood of South Shore. I learned not from him, who never bragged but from a mutual friend, that he had done remarkably well on the stock market.

Which only goes to show that money isn’t everything. Stan had three children, two daughters and a son; the boy went off to the University of Iowa, where at 20 he had a breakdown from which he would never recover. He was, I believe, diagnosed as on the edge of schizophrenia. He couldn’t hold a steady job, would live much of his life in halfway houses, and would be a constant worry to his parents. Curse of all curses, this permanently afflicted son made Stan into something of a tragic figure.

We met every six or so weeks, along with a third friend from college fraternity days, for lunch, at which he would arrive in his sleek black Mercedes. A more scrupulous friend than I, he would call me usually at least once a month. I don’t recall initiating many calls with him. He came to realize, as did many a pre-med and pre-dental student, how poorly educated he was, and in his fifties enrolled in great-books courses at the University of Chicago night school. At our lunches we often talked about Plato and other such subjects. Stan also began to talk about health, in particular his own, which seemed to be under attack from various quarters. He had trouble with his back, his legs, his breathing. He had taken some bad falls.

Stan and his wife had to abandon their house because neither could any longer negotiate the staircase to the second floor. Toward the end, his kidneys went, and he was put on a regular schedule of dialysis, which meant long sessions at a nearby hospital. He used the time for reading, but no improvement turned up. I learned of his death, in an intensive care unit, from a friend.

At one of our last lunches together, he showed me, on his phone, a photograph of his shattered glass shower door, through which he had fallen. I couldn’t, I still can’t, get it out of my mind. Each morning as I exit my own shower, I cling to my own shower door and think of Stan. Dead, I think, and not coming back.

_____________

On my last phone call from David, he told me that he had arranged an assisted suicide in Switzerland, for which he was to depart later in the week. I thought to attempt to argue him out of it but quickly decided not to. Instead I said, “You’ve been a small blessing in my life.” To which he returned, “And you’ve been a large one in mine.”

For the previous four or so years, David had been doing all he could to forestall the advance of Parkinson’s disease, even taking boxing lessons and installing a heavy punching bag in his bedroom. He used to drive to meet me for our bimonthly lunches; then, unable any longer to drive, he began to take the El; when that became impossible, I drove to pick him up and return him home to his Near North apartment. Then the Parkinson’s took a radical turn for the worse. His eyesight was affected, he could no longer read, his emails to me were blotched by sad misspellings. He was a man who always fancied control over his own life, and the disease deprived him of all control. Time, he concluded, to check out.

I knew David before he knew me. We didn’t go to the same high schools, but he, entrepreneurial from early youth, earned money taking group photographs of the clubs and fraternities at the highly socially organized Senn High School that I attended. (His father was a professional photographer.) Only later, at the University of Chicago, did we make a real connection. He had been there before I transferred from Illinois, and when I called to ask him where I might live on campus, he said, “How about with me?” With him meant sharing a three-room suite in a rather broken-down fraternity called Phi Psi that took in borders. We would each have a bedroom with a sitting room of sorts shared between us. The location and price were right. Sure, I agreed, why not?

In those years, the University of Chicago had only one quota—that on attractive girls, or so I came to believe, for it appeared to allow no more than one in every year. David, fortunate fellow, had one of them, a blonde named Dotti Cayton, as his lover. Long nights I sat in my room, trying to make up for all the reading I hadn’t done earlier in my life, while David and Dotti went at it happily away in his. Their last year in school, she became pregnant, and they married.

Ever the entrepreneur, while in college, David, along with an older man outside school, organized two big-time jazz concerts, one of which ran in Chicago’s Civic Opera House. He also attempted to sell neckties to his fellow students, a mistake at the habitually, the all-but-militantly, unkempt University of Chicago. So slowly did the neckties sell that at one point David and I began to play gin rummy for them.

After college, David went to DePaul Law School, soon after which he and Dotti moved to the West Coast, to Long Beach, California. We lost touch then and only regained it some 40-odd years later, when one night he showed up with a woman (not Dotti) at a reading I gave at a Barnes & Noble shop in downtown Chicago. At that point, we restarted our friendship and began our monthly lunch meetings.

David had done well in business in California, as an attorney, real estate developer and syndicator, and founder of Fast Funding, a mortgage-loan business. His looks had changed. I remember his telling me about the first time he had visited Dotti in her family’s very Gentile neighborhood in Indianapolis. He drove up in his green Ford convertible, with his dark hair, deep tan, sunglasses—the very notion of the flashy young Jew. He had now lost that hair, and his nose seemed larger than I remembered it, and become the very notion of the older Jew. At our first lunch meeting, I learned that Dotti had died of pancreatic cancer. They had had three children together, two girls and a boy. One of his daughters, in a case of false-memory syndrome, under therapy had accused him of molestation, which saddened him deeply.

At our lunches, I discovered David was fascinated by the question of what constituted human nature. Here greed, he felt, was not to be discounted. His conversation tended to be conducted on a fairly high level of generality, though punctuated by interesting facts. He once told me, for example, that on occasion he would give $100 to a homeless person. “It makes his day,” he said, “and with it mine.”

As a success himself, David had taken to giving advice, though not, I’m pleased to say, to me. In his obituary, his penchant for mentoring was underscored. At one point he sent me, via email, a Zoom session he put on for his children and grandchildren, whose major point was that, with the expenditure of common sense, one’s life could be under control and success not far away. Tell that, alas, to Parkinson’s.

_____________

My friendship with Gary began with proximity. He and his wife Rose (known by all as Posey) acquired the apartment next to ours on the third floor of a six-apartment co-op in Evanston. He was 52, she 40, and they were childless and had pledged to the co-op board that they would have no children. Less than a year later they did, a son named Joseph, who would suffer from attention deficit disorder.

Gary had been a teacher of philosophy at the University of Indiana at Indianapolis. Posey was among his students. He had grown up in Indianapolis, went to university at Bloomington in the state, and later to the University of Iowa for his doctorate, which he never completed. As I was to learn, if his son had an attention deficit disorder, Gary might have been said to have had an ambition deficit disorder.

Posey suffered no such deficit. Along with Gary, she opened a shop in Skokie selling women’s designer shoes at discount prices. The shop was an immense success. They departed our co-op and bought a grand house in the posh suburb of Winnetka. The two ran the business working 10-hour days seven days a week, and after a decade or so retired with enough money not to have to work ever again. Which suited Gary fine, his wife not.

Born for retirement, Gary now spent his days in his bathrobe, reading novels and not doing much else, which put his wife off enough eventually to divorce him. He moved back to Evanston, she off to southern California. Not long after, owing to his heavy smoking, he was afflicted with a heavy case of COPD, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He spent the last years of his life lashed to one or another kind of oxygen machine, yet never once, in all my conversations with him, complained about this full-time torture.

Gary would occasionally visit our apartment, but with his respiratory difficulty, travel became a heavier and heavier burden for him. I would sometimes run errands for him, but his son chiefly looked after him, as did his divorced wife, who kept a small apartment in Chicago after having moved to California. We checked in with each other by phone at least once a week, our conversations heavily punctuated by laughter. He was left-wing (in his obituary, “a donation to the Southern Poverty Law Center” is mentioned) though we never talked politics, not even about Donald Trump. On our last phone conversation, he did not so much say as call out, “You’re my best friend,” which much moved me.

We entered into a long-standing gambling relationship, betting piffling sums—$3, $5—on the Super Bowl, the World Series, the major tennis tournaments. If he ever got $5 or more ahead, he would instruct me “not to leave town.” He died owing me $2. One morning in his bed, the next difficult breath did not arrive, he gagged, choked, and died.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle puts an unspecified limit on the number of true friendships one can maintain. One cannot have “a friendship of the complete type with too many people,” he notes, having said earlier that old people do not seem to make friends easily. He underscores three kinds of friendship: pleasure-friendships, virtue-friendships, advantage-friendships. My four recently deceased friends all came under the first category, and I am too far advanced in life to have, or cultivate, friends in Aristotle’s second and third categories. With the death of these four men, I find myself running out of friends. I count two, maybe three, close friends remaining to me. “A wish for friendship may arise quickly,” wrote Aristotle, “but friendship does not.” Best to be grateful for the dear friends one has had and live off the rich memories those friendships provided. “Our dead are never dead to us,” wrote George Eliot, “until we have forgotten them.”

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.