Steven Wilson’s The Lost Decade1 is not just a book—it’s a requiem. It’s a mournful recounting of a moment when the education-reform movement, particularly the “no excuses” charter school model, seemed poised to deliver on an audacious promise: With focus, energetic effort, and commitment, schools could close the achievement gap between black and white students, lift low-income children out of poverty, and rewrite the script of American education.

For a brief, shining moment, we had it right. And then we lost our nerve. Wilson’s book, a meticulous autopsy of this rise and fall, is both a sympathetic chronicle and a call to a reckoning. The tragedy isn’t that “no excuses” failed—it’s that we convinced ourselves that it did.

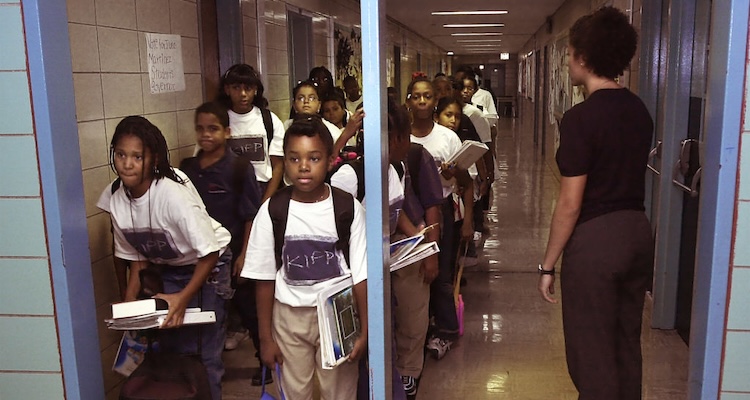

Let’s rewind the tape. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the first charter schools were opening and promising to be “engines of innovation” that would shake American education from its somnambulance, a new breed of inner-city school emerged: unapologetically rigorous, laser-focused on results, and built on the insistence that poverty need not be destiny. Schools like KIPP (the “Knowledge Is Power Program”), Achievement First, Uncommon Schools, YES Prep, and the Noble Schools didn’t just talk about high expectations—teachers and staff embodied and enforced them. Stealing a page from the era’s “broken windows” policing model, these schools sweated the small stuff. There were crisp school uniforms, homework assignments every night, students sitting up straight with eyes tracking the teacher, along with carefully crafted lessons and an ambitious curriculum. No more hand-wringing and no more alibis to explain away our multi-generational failure to adequately educate minority children and lift families out of poverty. More than a charter school model, no-excuses was a rallying cry: No child is a failure. We, rather, have failed children.

Start-up schools and youthful education-reform outfits such as Teach for America (TFA) became media darlings. Their scrappy, can-do spirit captivated journalists who portrayed them as underdog heroes set against a broken, indifferent system. It’s almost painful today to watch a profile of KIPP’s founders, David Levin and Mike Feinberg, which aired on 60 Minutes 25 years ago. Mike Wallace, following them as they knock on doors in Houston to win over skeptical parents, marvels at how hard work and KIPP’s lively school culture enabled poor black and Hispanic kids to academically rival their privileged peers. “It’s a public school unlike any you’ve ever seen before,” Wallace gushes. TFA, meanwhile, garnered glowing coverage in outlets like the New York Times and TIME magazine, which dubbed its young, elite university-trained corps “new civil rights leaders” and showcased their two-year stints in underserved classrooms as a generational crusade.

Those earlier ed reformers and school founders provided more than heart-warming anecdotes about kids from housing projects walking onto Ivy League campuses. Wilson brings receipts. Studies from Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) offer robust evidence of extraordinary academic gains in the networks of urban charter schools that sprang from those pioneering efforts that adhered to the no-excuses model. Students in those schools were found to have gained annually the equivalent of 40 additional days of learning in math and 28 in reading compared with their peers in the public schools where they would otherwise have been warehoused. Gains were most pronounced among disadvantaged populations—black, Hispanic, and low-income students—narrowing achievement gaps in cities like New York, Houston, Boston, and Washington, D.C.

Then came the fall. Charter schools fell victim to the excesses of wokeness long before DEI and critical race theory became political flash points. The education-reform movement lost its spine as social-justice madness led to crippling self-doubt. Critics, many of them well-meaning, began to pick at the edges of the no-excuses model. Was it too strict? Too militaristic? Too “white” in its norms? Was it fair to demand so much of kids already burdened by poverty’s weight? These questions weren’t new; they had dogged the movement from the start. But in the 2010s, amplified by social media and the cultural shift toward “equity” amid the rise of Black Lives Matter, the critiques gained traction among the youthful and well-educated reformers who had birthed the movement. The change was sudden and disorienting. The very things that had made the no-excuses approach work—its insistence on order and high standards—were recast as flaws or, worse, racist. Imposing middle-class norms on children of color was condemned as white supremacy.

By 2020, amid heightened scrutiny following George Floyd’s murder and a broader push for racial equity, KIPP announced the retirement of its iconic “Work Hard. Be Nice.” slogan, a mantra that had defined its culture of high expectations and civility since 1994. In a public letter to alumni that read like the product of a Maoist struggle session, Levin wrote, “As a white man, I did not do enough…to fully understand how systemic and interpersonal racism, and specifically anti-Blackness, impacts you.” The slogan reflected “white supremacy and anti-Blackness,” supported the “illusion of meritocracy,” and “suggested compliance and submission.” “Working hard and being nice is not going to dismantle systemic racism,” KIPP announced in a subsequent statement.

Even before Floyd’s death, a cultural wave was sweeping through schools, universities, and reform movements with a fervor bordering on religious zealotry. Books like Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist (2019) and Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (2018) became required reading for educators, administrators, and students. And their ideas permeated teacher training and district-wide equity initiatives. Kendi’s notion that there is no neutral ground in the fight against racism—one is either actively “antiracist” working to dismantle systemic inequities, or complicit in perpetuating them—pushed schools to adopt sweeping policies, from mandatory anti-bias training to revising curricula with “dismantling systemic racism” as a core theme. DiAngelo’s concept of “white fragility” framed any resistance to these changes as evidence of ingrained racism, creating a chilling effect that made dissent tantamount to moral failure.

The most bizarre artifact of this ostensible racial reckoning was the widespread circulation of the work of a white diversity trainer named Tema Okun, who branded traits such as “perfectionism,” a “sense of urgency,” and “worship of the written word” as hallmarks of “white supremacy culture” to be eradicated. Okun’s framework recast the strengths of high-performing urban charter schools (and schools more broadly)—discipline, focus, urgency—as liabilities, as if expecting kids to show up on time or strive for excellence was somehow a racial affront. Okun “doesn’t put forward any evidence or arguments in favor of her claims,” noted the progressive writer Matthew Yglesias, who dismissed the framework as “really dumb” while noting ruefully that it was “sloshing around quite broadly in progressive circles.”

Wilson details how these anti-intellectual ideas raced through charter schools and districts nonetheless, ending selective admissions for advanced programs and introducing “culturally responsive teaching” tailored to students’ racial and cultural identities. New York City public school administrators were trained on Okun’s framework by the schools chancellor himself. Seattle Public Schools established “racial equity teams,” devoted to the idea that the U.S. is a “race-based white-supremacist society,” and urging white teachers to “bankrupt [their] privilege in acknowledgement of [their] thieved inheritance.” The nonprofit Center for Black Educator Development received nearly $20 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Bezos Family Foundation, and corporate donors to promote its “Anti-Racist Guide to Teacher Retention,” which describes teaching as “a political act” that “can upend white supremacy and a racist history of using education as an oppressive social force and schools as oppressive social enforcers.” The public-education system itself, according to the widely quoted work of Bettina Love, is “invested in murdering the souls of Black children” through “systemic, institutionalized, anti-Black, state-sanctioned violence.” The education-reform movement had been founded and fueled by a sense of shame over a chronic and stubborn “achievement gap” between white and black students. Now any mention of it was itself racist since the very concept of an achievement gap was an example of “centering whiteness.”

_____________

The Lost Decade is a history, not a memoir, but Wilson was himself a casualty of this collective madness. He was defenestrated from Ascend, the Brooklyn-based charter school network that he had founded and led for more than a decade. Wilson had grown it into a network of 15 schools serving 5,500 low-income students of color in some of the borough’s most challenged neighborhoods, including Brownsville. In September 2019, he published a blog post expressing concerns that “as schools strive to become more diverse, equitable, and inclusive…there is the growing risk that these imperatives will be shamefully exploited to justify reduced intellectual expectations of students.” He rejected the growing disdain for academic achievement implicit in Okun’s fatuous litany. Citing works by Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King Jr., and James Baldwin, Wilson wrote, “How tragic it would be if any child was taught that a reverence for the written word was a white characteristic.”

Some staff interpreted his essay as racially insensitive or aligned with “white supremacist” ideology. A petition signed by dozens of Ascend employees accused him of perpetuating harm, and the controversy soon drew national attention. Facing pressure from his board, which was cowed by the broader equity movement of the hour, he was pushed out of his role as CEO.

Wilson doesn’t linger on his ouster or even mention it, but its shadow looms. This book is his rebuttal—not to his critics at Ascend, but to the ed-reform movement’s surrender to the social-justice left. He’s not here to apologize; he’s here to say we were right the first time. His personal stake gives the manuscript a quiet ferocity. He’s not just chronicling a movement’s demise but fighting for its soul. Nor does he pull punches. He argues that however fair or legitimate some aspects of the critique might have been, it snowballed into a kind of moral panic, one that infected even the charter sector’s staunchest defenders. Networks began to soften their edges, dialing back the discipline, rethinking the sweat-the-small-stuff ethos that had built those remarkable gains in student achievement in the first place.

By the late 2010s, the movement was fully under siege from within. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, the infection caught earlier in the decade started to rage in the bodies of char-ter school networks. The extent of the damage became clear when state testing, suspended for Covid, resumed in 2022. Since then, results have either failed to recover or have declined even further. Many of the era’s charter school highfliers now perform no better or worse than the district schools they were created to compete with.

The decade was lost not because the model broke, but because we broke faith with it. Poverty, racism, trauma—these are real, but they are not an alibi for illiteracy and innumeracy. The response was to provide structure, rigor, and a school culture of high expectations that defied the fatalistic thinking so endemic to American public education. And it worked.

_____________

And yet, we let the narrative shift. We let the loudest voices—often those least affected—convince us that the model was somehow unjust. So where did it go wrong? Wilson points to a few culprits. The rise of progressive pedagogy, with its emphasis on student autonomy over adult authority, clashed with the no-excuses ethos. He methodically dismantles the evasions that have undermined urban schooling: a therapeutic turn that replaced academic rigor with emotional validation; technological fantasies that promise salvation through software; an instrumentalist view that sees education merely as a pipeline to jobs rather than an intellectual endeavor; and, of course, the political capture of schools by activists who prioritize ideology over instruction.

Yes, it was imperfect. Yes, it could feel rigid, even stifling in the hands of less-capable teachers. But the structure of no-excuses charter schools wasn’t the problem—it was the point. Kids in chaotic neighborhoods and failing schools didn’t need more freedom; they needed guardrails. They needed adults who believed in them and cared about them enough to demand more of them.

Don’t take Wilson’s word alone. When the history of the education-reform movement is written, its leading figure will almost certainly be a man named Doug Lemov, whose seminal book Teach Like a Champion (2010) has shaped pedagogy beyond the charter sector, even internationally. A former teacher, principal, and charter school leader, Lemov honed his insights managing Uncommon Schools, a no-excuses network, where he observed, catalogued, and described teaching techniques that boost student engagement and achievement in high-poverty settings.

Lemov recently told me about his visit to what was once a stellar charter school in a small Northeast city. It was the kind of school, he said, where not long ago, parents could send their kids and know they would be physically safe and their education would be taken seriously. “I went back to that school in November [2024], and it was utter chaos. Just no learning happening,” he said. The school leaders told him that they “weren’t really sure that adults should be telling young people what to do.” Moreover, they were busy “dismantling systems of oppression,” which Lemov understood to mean orderly, teacher-led classrooms, students lining up for silent hallway transitions, and other standard features of no-excuses schools, and well-run schools in general, which had now fallen into disrepair and disrepute and even become an object of derision.

“My take was, whatever systems of oppression you think you’re dismantling, they’re a lot less oppressive than the chaos that is going on in this school right now,” Lemov told me. “And you should reassemble them as quickly as you can.”

1 Pioneer Institute Inc., 380 pages

Photo: Chris Hondros/Newsmakers

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.