Ladies and gentlemen, start your engines! As we await off-year elections in Virginia, New Jersey, and New York City, the 2026 midterm campaign is well underway. Fundraising is humming along. The map is coming into view. And candidates are jumping in.

One key matchup is set: Former Governor Roy Cooper, a Democrat, will battle RNC Chairman Michael Whatley for North Carolina’s open Senate seat. And the stakes are set high. “The decisions we make in the next election,” Cooper said in his July 28 announcement video, “will determine if we even have a middle class in America anymore.”

Easy there, Roy. The middle class survived the Great Depression, World War II, and disco. It will survive 2026.

But the Republican trifecta—control of the White House, House of Representatives, and Senate—may not. Democrats need to net three seats to win the House and four seats to win the Senate. Conventional wisdom holds that they’re on a path to win the lower chamber of Congress but face a steeper climb on the other side of Capitol Hill.

The truth is that any outcome is possible.

Democrats could win full control of Congress. Or they could split the House or Senate. Or they might fail to win a majority anywhere. Uncertainty reigns, because Democrats face structural obstacles as well as a fully engaged President Trump. He’s determined to avoid a repeat of his first midterm, when Democrats won 41 House seats and promptly impeached him twice. He’s hoovering up money—the GOP cash advantage is huge—and endorsing candidates early to avoid costly infighting. To secure his legacy and prepare Republicans for the 2028 presidential campaign, Trump must stave off a Democratic takeover.

The odds are against him. Polymarket shows a 70 percent probability that Democrats will win the House, with a similar chance of Republicans maintaining the Senate. History backs this up. Since the New Deal, the president’s party has gained House seats in just three midterms: 1934, 1998, and 2002. More recently, voters have opted for change in 11 of the past 13 elections.

Midterm results are highly correlated with presidential approval. And Trump’s rating is middling. With a job approval of 46 percent, according to the RealClearPolitics polling average, Trump is more popular than he was at this point in his first term. He’s around where George W. Bush and Barack Obama were at similar junctures in their second terms. The problem? Both Bush and Obama lost Congress the following year.

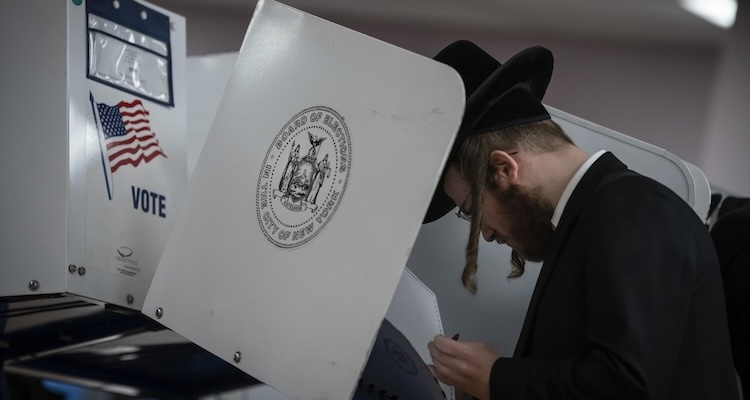

But Republicans can take solace in the Democrats’ woes. The party is leaderless, rudderless, and cash-poor. Democrats haven’t been this unpopular in 35 years. Their lead in the generic ballot is paltry. They bounce from issue to issue, defending illegal immigration in the morning, trans athletes in the afternoon, NPR and PBS in the evening, and DEI after dinner. They’re about to elect an anti-Semitic socialist as mayor of New York. Neither Joe Biden nor Kamala Harris is leaving the scene. And the 2028 bench isn’t impressive.

The Cook Political Report with Amy Walter counts 18 House seats as toss-ups. Democrats hold 10 of them. The Cook report says a single Republican-held seat—Nebraska’s Second District—is “lean Democrat.” The Nebraska seat, currently held by Representative Don Bacon, is one of three districts that split their votes between Kamala Harris and a GOP congressman. The other two are New York’s 17th (Representative Mike Lawler) and Pennsylvania’s First (Representative Brian Fitzpatrick). But a Democratic sweep is not guaranteed. Though Bacon’s retiring, Lawler and Fitzpatrick are strong candidates who won reelection last year by 6 points and 13 points, respectively.

Mid-decade redistricting may also boost Republican strength. At this writing, Texas Democratic state legislators have fled Austin to delay a GOP gerrymander that would result in five additional Republican-leaning seats. Ohio also plans a mid-decade redrawing of the congressional map. New Hampshire and Indiana might follow suit. The goal: provide a cushion for Republicans defending their narrowest House majority in nearly a century. Democrats in California, New York, and Illinois hope to thwart Republicans with their own partisan gerrymanders.

This will be harder than it sounds. First, blue-state governors would have to override independent redistricting commissions. Then they’d have to seek further advantages in maps that already highly favor them. Take California, for instance. Trump won 38 percent of the Golden State vote in 2024, yet Republicans make up only 17 percent of its House delegation.

The GOP is better positioned in the Senate. Susan Collins of Maine is the lone Republican up for reelection in a state Kamala Harris won. This matters because Collins is the only Republican who can win statewide, and Senate races in midterm cycles have often tracked with prior presidential outcomes.

In 2018, for example, Republicans held the Senate by picking off red-state Democrats in Indiana, Florida, and Missouri. Then, in 2022, Democrats protected their majority by defeating Republican challenges in Georgia, Arizona, and Pennsylvania. All three states had gone for Biden in 2020.

The good news for Republicans, then, is that Trump won the states whose Senate races Cook Political Report scores as toss-ups: Georgia, Michigan, and North Carolina. And Georgia and Michigan would be Republican pickups.

The battleground could expand, however. Senator Joni Ernst of Iowa might retire, opening another seat. Texas Republicans might nominate a weak candidate instead of incumbent Senator John Cornyn. And Democrats would like to mount a comeback in Ohio, if former Senator Sherrod Brown challenges Senator John Husted, who replaced JD Vance in January. Such possibilities are the stuff of Chuck Schumer’s dreams.

But dreams can go poof. Trump won Ohio by 11 points last year, and Brown lost to Bernie Moreno last year by 3 points. Trump won Iowa by 13 points, and the Hawkeye State hasn’t sent a Democrat to the Senate since 2008. Trump won Texas by 16 points—and the Lone Star State hasn’t elected a Democratic senator since 1988.

Republican chances of defying political gravity depend on two factors: inflation and independent voters. The 2022 and 2024 elections were reminders that inflationary environments are toxic for incumbents. To preserve his majority, Trump must count on a full-employment economy where incomes run above inflation. While wage growth exceeds inflation for most workers, the gap is small. Inflation is Trump’s worst issue. He can’t afford to make it worse.

Nor can Trump snub independents. He hasn’t won the independent vote since 2016, and that has cost him and the GOP. In 2018, Republicans lost independents by 12 points and suffered. In 2020, Trump lost independents by 13 points and went into exile. In 2022, Republicans narrowed the Democratic edge among independents to two points—enough to win the House but not the Senate. In 2024, Trump lost independents by three points but more than covered the deficit with expanded Republican turnout.

A double-digit loss among independents is the fastest way to end the Republican majority. Where does Trump stand? He’s at 30 percent approval among indies in the YouGov/Economist tracking poll. The IBD/TIPP poll has him at 32 percent support. The Quantus Insights poll is more favorable to Trump (and, in 2024, more accurate). It puts him at 38 percent among independents, below where he needs to be.

Staunching losses among independents requires focusing the agenda on lowering costs. But staying on topic has never been Trump’s style. His strategy is to polarize the electorate over social and cultural issues, especially immigration, and mobilize low-propensity voters. It has worked for him before but carries huge risks. If Trump’s not careful, independents will join energized Democrats in a repeat of 2018. And what starts as a blue trickle could turn into a flood.

Photo: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

We want to hear your thoughts about this article. Click here to send a letter to the editor.